The 1997 UNICEF lecture was given by Peter Adamson at the Church House Conference Centre, London, on June 16th, 1997.

A tribute to the life and work of Jim Grant, the lecture was later republished in Jim Grant: A UNICEF Visionary, edited by Richard Jolly with an introduction by President Jimmy Carter.

I want to devote this 1997 UNICEF lecture to the telling of a story.

I think it’s a remarkable story. And I hope that in half an hour or so you will agree.

The facts of the story have been recorded from time to time in the media. But the story has never been told.The title of the story is The Mad American. And its central character is James Pineo Grant.

At the time the story opens, Jim Grant is 57 years old and already has a distinguished – apparently conventional – career behind him: Deputy Director of the United States aid programme, head of various of US aid missions, President of a prestigious Washington think-tank, Trustee of the Rockefeller Foundation.

But our story opens in 1979, when President Jimmy Carter nominates Jim Grant to become the new head of UNICEF.

UNICEF needs little introduction here. Headquarters in New York. Offices in nearly every country. Several thousand employees. National Committees in all industrialised countries. Running programmes to help children throughout the developing world.

Changing gears

The 1980s open and the new head of UNICEF moves into his New York office overlooking the East River.

He begins conventionally enough. Travelling. Listening. Learning about the organisation.

The first sign that something different is about to happen comes at a place called Sterling Forest. It’s a rather plush, corporate conference centre about two hours north of New York City. Not really UNICEF’s style.

Jim Grant has invited maybe a hundred people. Mostly UNICEF staff from around the world. A few outsiders like myself. The idea is to discuss UNICEF’s future – and for the new Executive Director to outline his own thinking on the subject.

Well, over the three days of the meeting, Jim Grant does outline his thinking. But he succeeds mainly in mystifying and alarming people.

The phrase he uses again and again is that he wants UNICEF to shift gears. He feels the organisation has been going along nicely in second. Now he wants to see a rapid shift to third, and then fourth.

People exchange glances across the room.

He isn’t interested, he says, in incremental increase. He doesn’t want to know about a 5% or 10% a year improvement in UNICEF’s performance.

What he wants is a quantum leap. He wants UNICEF’s impact on the world to increase tenfold, fifty fold, a hundred fold. And he wants it to happen quickly.

Smiles are still being exchanged across the room. But the smiles are growing distinctly more nervous.

So how do we make this quantum leap, he asks. How do we shift gears? How do we punch above our weight? How do we get more bang for our buck?

We have a few hundred million dollars, he says. Three or four cents for every child in the developing countries. We can’t change the world with that.

In any case, he continues, what changes the world isn’t budgets and projects and programmes.

What changes the world, is major shifts in thinking, brought about by advocacy, new ideas, new visions.

And putting all this together, and ever one to mix a metaphor if he possibly could, the new Executive Director says that UNICEF’s main objective under his leadership will be leverage in the market place of ideas. Only being an American of course he said lēverage.

In the days and weeks that followed Sterling Forest, alarm bells rang out in UNICEF offices across the world.

Shifting gears. Quantum leaps. Advocacy. Changing the world. Leverage. Market place of ideas. Had anyone told him that this was UNICEF?

And as always on such occasions, an informal consensus rapidly developed in the bars and the corridors and the coffee lounges.

And the word at Sterling Forest was – American. He’s very American.

The big idea

Within months, the big idea that Jim Grant is looking for – the idea that would allow UNICEF to multiply its impact in the world – is almost handed to him on a plate.

Or rather in a paper. It is contained in a lecture given at a conference in Birmingham, England, by a Dr Jon Eliot Rohde.

I can’t do justice to that extraordinary lecture here.

But let me try to sum up in a sentence what it was about it that changed the course of UNICEF for the next fifteen years.

It was the proposition that more than half of all the death and disease among the children of the developing world was simply unnecessary – because it was now relatively easily and cheaply preventable.

Let me also try to telescope the argument behind this contention.

About 14 million young children were dying in the developing world every year. And the great majority of this death and disease could be laid at the door of just five or six common illnesses – measles, tetanus, whooping cough, pneumonia, diarrhoeal disease – often in conjunction with poor nutrition.

These were the same diseases that had taken a similar toll in Europe and America right up until the early part of this century.

The difference was that there were now low-cost means of prevention or cure for almost all of them.

Vaccines had long been available to protect children against measles, tetanus, whooping cough, polio. There had been recent technological advances in such areas as heat-stability, and the costs had fallen dramatically.

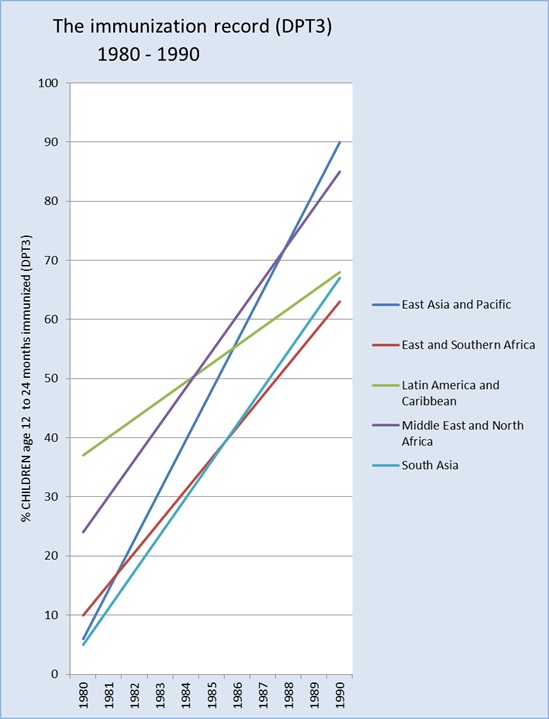

Yet only about 15% of children in the poor world were being immunised. And these diseases were still killing 4 or 5 million children every year.

Similarly, trials had proved that cheap oral rehydration therapy (ORT) could prevent most of the dehydration, caused by diarrhoeal disease, that was killing over 3 million children every year.

And it wasn’t just a question of saving lives – the sheer frequency of all these common illnesses saps the mental development and physical growth of even larger numbers of survivors.

And it was now so unnecessary.

The methods of prevention or treatment were tried and tested, available and affordable.

But they had not been put at the disposal of those who need them. The bridge has not been built between what science knows and what people need.

Now this analysis obviously drew on a large body of work in child health. And the person who perhaps contributed most to that work I hope is here this evening. He is Dr David Morley, then Professor of Child Health at London University, who has devoted much of his life to precisely this cause of building the bridge, of developing and promoting low cost methods of protecting children’s lives and health.

After reading the Birmingham lecture, Jim Grant spent a week or so with Jon Rohde in Haiti, being shown in flesh and blood what the lecture had shown in facts and figures.

When he got back to New York he knew that he had found his big idea. He knew how UNICEF was going to change gears and multiply its impact in the world.

Dr. Jon Eliot Rohde whose 1980 lecture in Birmingham, England, changed the course of UNICEF

A child survival revolution

September 1982. Jim Grant calls another meeting. A more modest affair. UNICEF headquarters in New York. A weekend. About twenty people. Senior UNICEF staff. Some outsiders.

The purpose is, once again, to brain-storm on UNICEF’s future role and direction.

But if what came out of the Sterling Forest meeting was alarmingly vague, what came out of the New York meeting was quite terrifyingly specific.

Gradually, Jim worked the meeting round to his big proposal.

He wanted UNICEF to launch a world-wide child survival revolution.

He wanted UNICEF to lead a campaign to halve child deaths across the developing world.

He wanted UNICEF to set itself the aim of cutting the toll of disease and disability on an unprecedented scale.

And he wanted to do it by means of a massive, focused, effort to make three or four low cost techniques like immunisation and ORT available to almost every child in every developing country.

The audacity of this proposition is almost impossible now to recapture.

At that time, UNICEF projects – anybody’s projects – in the developing world were reaching out to a few hundreds, occasionally thousands, of children in villages here and neighbourhoods there.

Now Jim Grant was talking about reaching out to four or five hundred million children in the developing world, and to the 100 million that were being born into it each year.

To begin with, he said that immunisation levels had to be doubled – to 40% by the mid 1980s. And then doubled again – to 80% by the end of the 1980s.

Then there was ORT – the salts and water solution that can prevent death from diarrhoeal disease.

At the time, the technique was virtually unknown. Jim said it must be put at the disposal of at least half the families in the developing world within a few years.

ORT and immunisation weren’t the only priorities. But they were what Jim liked to call the twin engines of a child survival revolution.

These were simply staggering proposals.

And it is impossible now, all these years later, to recapture the full sense of how extraordinary they seemed at the time. I couldn’t tell you how many times I heard the phrase – ‘he’s mad’ – in the days and weeks that followed.

The tanker and the speedboat

I too had read Jon Rohde’s original lecture. And I had devoted a good deal of the draft State of the World’s Children report for that year to what I thought was rather a passionate advocacy of its prescriptions.

But it was a hand-wringing piece. It was a ‘something ought to be done’ piece. And it wasn’t enough.

Jim wanted the report – about to go out in dozens of languages to every newspaper and magazine and every radio and television station in every country – to announce and launch the child survival revolution.

The Director of Information for UNICEF New York at that time was my good friend and colleague John Williams. He and I pleaded with Jim to think again. To consult more widely. To let people in the organisation have their say. To take just a few more months. To refine the idea before launching it into the world.

Jim would have none of it.

I remember arguing with him late one night and saying to him ‘this organisation is a 200,000 tonne vessel with a fifteen mile turning circle – it’s an oil tanker and you’re trying to drive it like a speedboat.’

I knew straightaway that it was entirely the wrong thing to say. His eyes lit up as he saw himself at the helm of a oil tanker, throwing the throttle, changing up a gear or two, watching the prow rise up in the water, taking off across the seas.

He went ahead with the announcement of the child survival revolution.

And again it is almost impossible to recapture the reaction.

But at the time you could see the shock on people’s faces. You could feel it in the canteens and the corridors.

Attempting anything on this scale was clearly mad. UNICEF would fall flat on its face. UNICEF couldn’t do it. Nobody could do it. The money wasn’t there. The roads and the transport systems weren’t there – the clinics, the vaccinators, the electricity supply, the fridges, the cold chains, the communications capacity – even the demand wasn’t there.

None of it was in place for action on this scale.

And even if it were – focusing everything on immunisation and ORT?

What about education, water supply, sanitation, housing, street children?

It seemed to be throwing out all UNICEF’s history and priorities – throwing away years of commitment to integrated development strategies, basic-services, and people’s participation.

It was reducing the prized complexities of development to the contents of a sachet and a syringe. It was top-down. It was technological fix. It was tunnel visioned. It was, as the World Health Organisation said, monofocal.

The reaction, in short, was overwhelmingly negative – inside UNICEF itself, inside the other UN agencies, in government circles, among development professionals and academics.

Turmoil

Some opposed Jim Grant out of fear of upheaval and failure, out of innate conservatism, out of not wanting comfortable routines to be disturbed.

Others had more legitimate concerns about the whole approach.

And there was hardly anyone involved at the time who did not have the most serious doubts about what Jim Grant was proposing.

And this story would be romanticised, untruthful, if I did not try to capture some of the turmoil of that time.

I myself was certainly sceptical. And my worries were perhaps not untypical.

Anyone who has worked in this field knows that development is the most subtle and complex of processes; knows that the answers are not primarily technological but political and social; knows, too, that there are great dangers to imposing simplified strategies from the outside.

Also, at a time when so many of the world’s poor were becoming poorer – as debt mounted, commodity prices fell, and aid declined – it did not seem right to be going into battle for vaccinations and oral rehydration salts alone. It felt like relinquishing the real struggle.

And, speaking for myself, I dislike and distrust simplicities and certainties, and sound-bites and single-mindedness. They are the close cousins of intolerance and imposition.

And yet …

There is a danger that complexity can itself be a kind of comfort, an excuse for inaction, a kind of liberal paralysis.

And many of us, I remember, were tired and frustrated with campaigning on a broad front and seeming to get nowhere.

And who could not be struck by the sheer unforgiveableness of millions upon millions of children dying and having their normal development undermined – when the means to prevent it were at hand?

It was as if a cheap cure for cancer had been discovered but no-one had bothered making it available. And if that comparison sounds far fetched, it is only because we are hearing it from the perspective of a rich society. If you look at the figures, the analogy is fairly exact.

And hanging over all this turmoil and doubt, was the sheer and obvious impossibility of UNICEF attempting anything on this scale.

Well … these were some of the considerations.

But for me the decisive factor was probably more trivial. I have always loved words and the English language. And if Jim Grant’s enemies were going to accuse him of monofocality then I was always going to be on his side.

So Lesley and I and many others decided that we would go with the mad idea, that we would help Jim Grant to run this one up the flagpole.

Oh yes, I was becoming more American every day.

Dark days

The early days were pretty dark.

There were many inside and outside the organisation who were scathing and hostile.

So much so that at this time Jim’s position was in some danger.

There was talk of getting rid of him. There were murmurs of mutiny in the ranks. There were rumours that his contract would not be renewed – the equivalent of the governments of the world firing Jim Grant as head of UNICEF.

And the organisation itself came round behind him only slowly. It turned out to be an oil tanker after all.

But turn it did.

The Executive Director has power to hire and fire, power to promote or pass over, power to include or exclude from inner counsels. These are the crude instruments of internal direction changing in any large organisation. And Jim used them.

But many more came around for better reasons.

There was the faultless public health logic of the case for making this attempt.

And there was the personality of the man himself. The idealism and commitment were so obviously genuine – in all the years I never heard anyone question this.

For all the grand plans, Jim Grant personally was devoid of self-importance. And for all the high profile campaigning that was to come, he never sought the spotlight for himself.

For Jim, it was only and always the cause.

And I believe that in the end it was this as much as anything else that won so many to his side.

And so, in the early and mid 1980s, work began on the grand plan.

Going to scale

The problem was essentially one of scale.

The world that Jim Grant came into, as the new head of a UN agency, was by and large a world of small scale projects, of pilot studies, field trials, research and demonstration programmes.

And the question he made everyone confront was – how do you go to scale? How do you take known solutions and put them into action on the same scale as the problems?

Now of course you can’t even think about reaching out to people on this scale without governments.

And that means you have to have political will.

If only the political leaderships of nations were committed, then of course these things could be attempted across whole countries – with aid from the international community and help from UNICEF and others.

Political will.

How many late night conversations have ended with the words ‘you can’t do anything without political will’?

How many plans and potentials have come to nothing for the lack of this political will?

Jim Grant’s response was: Well, we’ll just have to create the political will.

Creating the will

He began an astonishing odyssey. Over the next few years, he travelled many hundreds of thousands of miles and met with the great majority of political leaders in the developing world.

I am completely confident in saying that no one has ever held one-to-one discussions with anything like as many of the world’s Presidents and Prime Ministers as Jim Grant did in those years.

And these were not ceremonial meetings or photo opportunities.

He cut through all of that and made his pitch. He was never without his sachet of oral rehydration salts. And he was never without the key statistics for that country.

He would ask every President and Prime Minister he met if he or she knew what the country’s immunisation rate was, and how many of the country’s children were being killed and disabled by vaccine-preventable disease or dehydration, and how little it would cost to prevent it.

To see him in action in these meetings was truly astonishing.

He would tell heads of state that other countries were doing much better, or that their neighbours were racing ahead, or that he needed some far-sighted political leader to set an example to the whole world of what could be done.

He would point out to the President that economically his country was ten times more developed than, say, Sri Lanka, but had a far lower immunisation rate and a far higher child death rate.

He would sadly point out that the protection being given to children was lagging well behind what could be expected for a nation of this standing.

He would tell the President of Brazil – and go on Brazilian television to say – that Brazil was among the richest of the developing nations, but that it had one of the worst records in child health and child survival.

He didn’t complicate matters with other issues. For heads of state, he said, you have to pitch in with a simple, doable proposition. You appeal to their idealism, but you also tell them how they can drastically reduce child deaths at a cost they can afford and on a time scale that can bring them political dividends.

He cajoled and persuaded and flattered and shamed and praised. He offered aid money that he didn’t have, and he offered help that the UNICEF country office often wasn’t in a position to give.

And he back-slapped and shook hands with them all, whether democratic leaders or dire dictators.

He shook hands that were stained with blood, hands that had turned the keys on political prisoners, hands that had signed away human rights, hands that were deep in the country’s till.

Some of this, I and others were occasionally unhappy about, worried about the lending of UNICEF’s good name to corrupt and inhuman regimes.

But Jim’s answer was always the same. ‘We don’t like the President so the kids don’t get immunised?’ ‘You want to wait to launch the campaign until all governments are respectable?’

And he was shameless in other ways too. There were so many examples, but I have time only for one.

Sometime in the late 1980s Jim had had some peel off stickers made – printed with the words ‘child survival revolution’. We had been in the Dominican Republic together to see the President. And the President was so taken with Jim that he gave a grand dinner in his honour. There was the President, wearing a million dollar suit and flanked by three or four generals wearing more gold braid than you could carry.

The President asked Jim to make a speech. Half way through his pitch on what the President could do for the children of the Dominican Republic, Jim looked at the generals behind the President’s chair. Pausing, he reached into his pocket.

‘You know Mr President,’ he said, ‘the child survival revolution also needs it generals. And I now create you a five star general of the child survival revolution’ – and he reached over and began putting little stickers all over the President’s million dollar suit.

When we got back to our hotel, Jim’s wife Ethel turned to him and said ‘Jim, you are such a ham.’

Ham or not, I watched the President of the Dominican Republic on national television the next night and he was calling for the immunising of all the nation’s children and waving a little sachet of ORS at the camera.

“No one has ever held one-to-one discussions with anything like as many of the world’s Presidents and Prime Ministers as Jim Grant did in those years.”

Social mobilisation

Jim’s solution to the lack of resources and infrastructure for action on this scale was just as bold.

Everywhere he went he called for ‘social mobilisation’.

The job called for a massive reaching out – not only to ensure supply but to create demand.

And in most countries it clearly couldn’t be handled by health services alone.

Jim’s answer was to enlist every possible outreach resource in the society – the teachers, the religious leaders, the media, the business community, the army, the police force, the non-governmental organisations, the youth movements, the women’s organisations, the community groups.

UNICEF appealed to them all to get involved.

The strain on UNICEF offices was something entirely new.

Most responded magnificently. But performance now was measurable. There was a bottom line. What were the figures for immunisation and ORT? And how fast they were rising?

And there was no hiding place.

I think I can best illustrate this pressure by one other example.

Jim was constantly asking for progress reports from UNICEF representatives in every country. And on one occasion he asked the UNICEF representative responsible for El Salvador why the immunisation level there was low and static.

The representative replied that the country was in the middle of a civil war and that most of it was a no-go area.

Most people would have thought that was a reasonable answer.

Jim’s reply – said straight out – was: ‘well why don’t they stop the war so they can immunise the kids’

It was just the kind of remark that made people think he was unbalanced.

Jim Grant flew to El Salvador. He and the UNICEF staff in the country enlisted the help of the Catholic church and met with government and the guerilla leaders. And within a few months, both sides in the country’s civil war agreed to call three separate days of cease-fire so that the nation’s children could be immunised. And this happened ever year for several years until the war came to an end.

There were very few excuses that would satisfy Jim Grant for not reaching out to the children of the whole country. And a little thing like a civil war wasn’t one of them.

In any situation where a job looked impossible, Jim’s approach was always to look for leverage points. How can we ‘end-run’ this one was always his question.

And again, I have time for only the briefest of examples.

Soon after the assassination of Indira Gandhi, Jim flew to New Delhi.

He saw the new Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi. And he proposed to him that the immunisation of India’s children should be the living memorial to his mother, Indira.

Rajiv Gandhi agreed. And he had the monitoring of immunisation levels put down as a regular item at cabinet meetings.

Promotion and criticism

These examples are only an indication of the colossal amount of work done in these years to create the political will and initiate action on a nation-wide scale in country after country.

Backing all of this up was a major world-wide media campaign by UNICEF. A great many people were involved. Everybody in UNICEF had to become a promoter. And the annual State of the World’s Children report and, later, The Progress of Nations, were only the flagships.

But here the message was preached and the arguments made.

Here the organisation was primed and armed.

Here the figures were set out, the critics answered, the successes and failures recorded.

And it was all directed towards one end – helping to stimulate action on the necessary scale.

And the job was not only one of promotion. There was also a defence to be conducted.

You can’t expect to attempt something on this scale without criticism.

The critics said that the whole effort would be self-defeating, because it would only fuel population increase.

They said that the children being saved by vaccines or ORT would only die of something else because UNICEF wasn’t tackling the fundamental problems of poverty.

They said that by concentrating only on saving lives UNICEF was ignoring the quality of life of the survivors.

None of these points is valid. But they are all superficially plausible. And they were battles that had to be fought, year after year, article after article, reply after reply.

And at this time, Jim’s position – and the outcome of the colossal gamble he had taken – were still in doubt.

The only thing that could save it all was results.

First results

By the middle of the 1980s, those results were beginning to come through. Nations were beginning to make commitments.

And immunisation and ORT rates were beginning to rise.

Overall, the proportion of the developing world’s children who are immunised doubled to 40%

And the use of life-saving ORT rose from almost nothing to the point where the therapy was being used by over a quarter of the families in the developing world.

Already, these were results on an entirely unprecedented scale.

Now change like this doesn’t come about just because Jim Grant meets the President, or because the issues are put across to governments and the media.

UNICEF people all over the world, and their counterparts in governments and in several other UN agencies worked to make it happen, to translate the political will into practical action on the ground.

WHO, in particular, provided scientific advice on cold-chains and vaccine quality, and trained thousands of immunisation managers.

Hundreds of non-governmental organisations were becoming involved. Rotary International alone raised over $300 million dollars and mobilised its volunteers in a hundred countries.

There are many thousands of actors in this story, and I’m very conscious of leaving so many of them out of this account.

But the point is that Jim Grant and UNICEF were supplying the one ingredient that had always been missing – the new sense of scale, the push for political will, the mobilisation of so many other people and organisations in support of common, measurable, goals.

And as the figures rose, support began to swing behind Jim Grant.

Everywhere UNICEF National Committees, as well as fund raising and lobbying, made sure that governments took notice.

And at a time when aid was falling and all other UN budgets were being cut back, UNICEF’s budget was on its way to doubling to more than a billion dollars a year.

The critics fall quiet. The noise of internal battle begins to die down.

And the ORT and immunisation rates continue to rise.

Iodine and vitamin A

But as the world moved towards the 1990s, the size of the task also began to increase.

For example – it was established beyond reasonable doubt that lack of vitamin A was responsible for approximately 2 million child deaths a year – and for leaving at least a quarter of a million children permanently blinded each year.

It was a tragedy that could be prevented by vitamin A capsules – at a cost of about 2 cents per child per year.

By all the same reasoning that has taken UNICEF this far, this finding cannot be ignored.

Similarly, it also became established that the biggest cause of preventable mental retardation among the world’s children was lack of iodine in the diet.

New studies showed that iodine deficiency – a very little known problem – was affecting 50 million children under five. It was causing 100,000 infants a year to be born as cretins. It was causing tens of millions of children to have lower IQs, so that they were not doing as well as they should in school.

This tragedy, too, could be prevented – as it was in the industrialised nations – by iodizing all salt. The cost, in relation to the potential benefits, was negligible.

And this, too, simply could not be ignored.

It is not just that these were important problems touching large numbers of children. There are plenty of important problems facing the world’s children.

The point is that these were problems for which solutions were available and affordable. So much so that it was unconscionable not to put them into action, not to do what it was now so obviously possible to do. Morality must march with capacity.

A World Summit for Children

I can’t evade some small share of responsibility for the next mad idea.

To push for action on all of these fronts, Jim began looking for faster ways to create political will, to spell out to Presidents and Prime Ministers – and the public – what could be done.

October 1988. We were flying back to New York together. Jim began talking about organising an international conference to try to get all these things moving at the same time.

I told him the world was bored with UN conferences. They’re seen talk shops. There’s never any action afterwards. It would only be worth it if we could get Presidents and Prime Ministers to come together to talk about what could be done for children.

Well, the madder the idea, the more likely it was to appeal. And before we landed, Jim had decided to attempt a World Summit for Children.

Over the next eighteen months, he willed it into being.

UNICEF could not convene a summit of world leaders. But in a few months, Jim persuaded the Prime Ministers of Canada, Sweden, and Pakistan, and the Presidents of Mexico and Mali, to form a special committee to convene a World Summit.

He persuaded Margaret Thatcher and George Bush to come.

Soon, over 70 of the world’s Presidents and Prime Ministers had agreed to attend. It was to be the largest ever gathering of heads of state under one roof.

Then we ran into some problems.

Protocol was being handled by an inter-governmental committee. They announced that all the heads of state would have to make a speech – all seventy-odd of them. So there would be no time for any other speakers. Not even Jim Grant.

This defeated the whole point. We had thought they would be coming to listen to what could be done for children.

We had forgotten Adlai Stevenson’s warning that a politician is someone who approaches every question with an open mouth.

UNICEF protested. Jim was given 4 minutes to address the assembled world leaders.

The job could not be done in 4 minutes.

We tell them it will be interminably boring, all those speeches one after another. There must surely be a video. All conferences have a video.

They agree – maximum 12 minutes.

They also agree that Jim’s speech can follow directly after the film.

We have sixteen minutes to make the pitch.

I came back to London to see my friend and colleague Peter Firstbrook, a senior producer at the BBC. We had no time to shoot anything new. We began cutting and pasting past films that we had made together.

The film was written as one presentation with Jim’s speech. And it was screened to the assembled heads of state at the World Summit for Children. UNICEF also organised for it to be shown on national television stations in almost 90 countries on that same day.

The film was called “341” – named after the number of children who will die unnecessarily during the twelve minutes it takes to screen.

I know that many of you here tonight have used the film well over the years, and I thought you might like to know how it came into being.

Target met

The World Summit for Children convened in late September 1990 – and UNICEF and WHO were able to make the big announcement.

The target of 80% immunisation – the target that so many had said was impossible only a few years earlier – had been met across the developing world.

It was an absolutely vital announcement, not only for the millions of lives a year that immunisation was now saving but for the credibility it lent to the proceedings, and to all the other targets now being proposed.

Everybody at UNICEF worked frantically behind the scenes. New goals to protect children, including goals for iodine and vitamin A, were agreed. And all of the heads of state present committed themselves to drawing up nation-wide plans.

Over the next five years the pressure on UNICEF, on headquarters, on the country offices, on the national committees, was intense – to raise more funds, to lift public support, to keep governments up to their promises, to maintain and increase immunisation rates, to promote breast feeding, to step up the pace on ORT and vitamin A, to make sure that all salt is iodized.

A Score-card

I cut rapidly now to 1995, the most recent year for which figures are available. And I want to give you a brief score-card.

Almost all nations – one hundred and twenty nine in all – have now reached, and sustained, immunisation levels of 80% or more. About ninety of those countries have passed the 90% immunisation mark.

Compared with the toll in 1980, more than three million child deaths from measles, tetanus, and whooping cough are being prevented every year.

And the normal growth of many millions more is being at least partially protected.

Meanwhile the number of children being crippled by polio has fallen from 400,000 a year in 1980 to under 100,000 a year in 1995.

There is now every chance that before the year 2000 polio will have been eliminated from the face of the earth.

And as we sit here in London this evening, there are at least 3 million children in the developing world who are walking and running and playing normally who would be crippled for life by polio were it not for this extraordinary effort.

And what of the other main ‘engines’ of the child survival revolution?

ORT is being used in some form by about two thirds of all the families in the developing world – saving at least a million young lives a year.

Iodine deficiency, and the mass mental retardation it causes, is close to defeat.

Of the more than 90 developing countries with iodine deficiency problems, 82 have now passed laws requiring the iodization of all salt – and most are close to the target of 90% salt iodization.

In total, 1.5 billion more people are consuming iodized salt today than in 1990. And at least 12 million children a year are being protected from some degree of mental damage.

Vitamin A promotion is moving more slowly. But it’s moving. Seventeen developing nations, including some of the largest, have already eliminated Vitamin A deficiency and the deaths and the blindness it was inflicting on their children. And 24 more countries have now launched nation-wide programmes.

§

These are only the highlights of what was achieved during these incredible years. And all Jim Grant could think about was how much more there was to do. He was then 72 years old and showing not the slightest sign of slowing down.

Then came the news that Jim Grant was in hospital. And soon everybody knew that Jim had cancer.

The end

Operations followed. And chemotherapy. And radiation.

Throughout, he refused to concede anything to his illness. He almost never referred to it.

Once or twice I worked with him in the Sloane Kettering cancer hospital in New York as he waited to go in for his next session. His concentration on what we were doing was total.

And he refused to slow down.

In the last year of his life, when he was visibly ill and failing in body, he travelled tens of thousands of miles and held meetings with over 40 Presidents and Prime Ministers, building the political will to achieve the new goals that had been set at the World Summit for Children.

He still carried his ORS sachet. He still berated world leaders with figures and comparisons.

And he was still shameless.

He now also carried in his pocket a small dropper of liquid. Dropped onto salt, the liquid turned blue if the salt had been iodized. And at state banquets in capital cities across the developing world, Jim would wait for an appropriate moment and then ask the President or Prime Minister to please pass the salt.

§

Jim Grant died in a small hospital in upstate New York in February 1995.

The last few hours of his life were immensely moving.

It sounds like an over-dramatic figure of speech to say that someone fights for a cause until the last breath in his body.

In Jim Grant’s case, it was quite literally true.

In his last hours of that last morning in the hospital, as he drifted in and out of consciousness, he was still struggling to map out the strategy for the next Board meeting of UNICEF.

But for Jim the battle was at an end.

All around him in the hospital room were letters and cards from virtually every country in the world, including from many of the Presidents and Prime Ministers he had pushed and persuaded so hard.

On the cupboard by his bedside was a card from President Clinton. It said:

“I am writing to thank you from the bottom of my heart for your service to America, to UNICEF, and most of all to the children of the world”.

A few days later, a memorial service for Jim Grant was held at the Cathedral of St John the Divine on New York’s upper West Side.

It is the largest cathedral in the world. And it was full to overflowing with more than 3000 people who had come to pay tribute to the Mad American.

They included Hilary Clinton and several members of the Clinton cabinet who had flown in from Washington for the service.

I can’t list all the hundreds of tributes here.

Chinese Premier Li Peng wrote that Jim’s death “was an irretrievable loss to the children of the world.”

Nelson Mandela wrote to say that “his death is a great loss to each and every needy child in this world.”

Former President Jimmy Carter said that his nomination of Jim Grant to head UNICEF was one of the greatest and most lasting achievements of my Presidency.

And the New York Times, the paper that Jim had loved, mourned the passing of “one of the great Americans of this century.”

A place to stand

I have only been able to give the edited highlights of this story. And I have not told of some of the set-backs and disappointments, failures and mistakes.

I don’t know why the story is not better known. Perhaps it is because its beneficiaries were the sons and daughters of some of the poorest and most neglected people on earth.

No further comment is needed from me on the extraordinary years of Jim Grant’s leadership of UNICEF.

But I would like to add just one final comment on this story – and it is addressed particularly to Robert and his colleagues and to the many UNICEF people here tonight.

Jim Grant achieved what he did, as he said he would, by exerting leverage.

And when the principles of leverage were first expounded two thousand five hundred years ago, Archimedes summed it all up in one famous phrase: ‘Give me a place to stand and I will move the world’

Jim’s place to stand was UNICEF. He could not have done what he did standing in any other place. Not as an American politician, not as the head of a large non-governmental organisation, not even as the head of any other UN agency.

UNICEF is a household name in virtually every country of the world. It is a name that commands respect and affection everywhere. It is the name that opened the doors to Jim Grant. And it is the name that predisposed those inside those doors to listen.

The name of UNICEF, and all that it means world-wide, has been built up by many people. But perhaps most of all by those who make UNICEF a unique organisation – by the National Committees and their workers and volunteers across the industrialised nations – those who work for them and those who support them – you built for Jim his place to stand.

And he did move the world.

Back to top of page